MURMANSKROVANIEMIKIRKENES

MURMANSKROVANIEMIKIRKENES

Morten skriver: Vi kan begynne med MRK. Skal se om jeg finner noe dokumentasjon dere kan bruke. Men dere kan også avfotografere selv hvis dere vil. Og sjekker om har pdf, men ikke sikkert at det finnes.

Når der gjelder tekst. Hanna horsberg hansen skrev en anmeldelse i Nordlys. Og Jonas Ekeberg skrev noe til en gruppeutstilling på Preus museum. Tror de bildene også var med i utstilling Jan Erik lundstrøm turnerte for sdg/sds, men husker ikke om han skrev noe spesifikt. Skal lete men blir en slags utgraving.

Skisser til dokumentasjon nov 2024 Her kommer noe som dere kan tygge på foreløpig. Alt annet må produseres på nytt eller letes etter, så kanskje vi kan snakke om det når dere vet formatet på arkivet.

Hilde: I tillegg har jeg bedt om boka 'Circulating Sites' som er relevant... Men igjen, er det kanskje like relevant å vise flere av bøkene hans, fordi jeg tenker at det er det at han fotograferer i området og har bygget hele sin fotografiske praksis på det, som er hva som er bra og interessant.

Murmanskrovaniemikirkenes

Murmanskrovaniemikirkenes

Morten Torgersrud

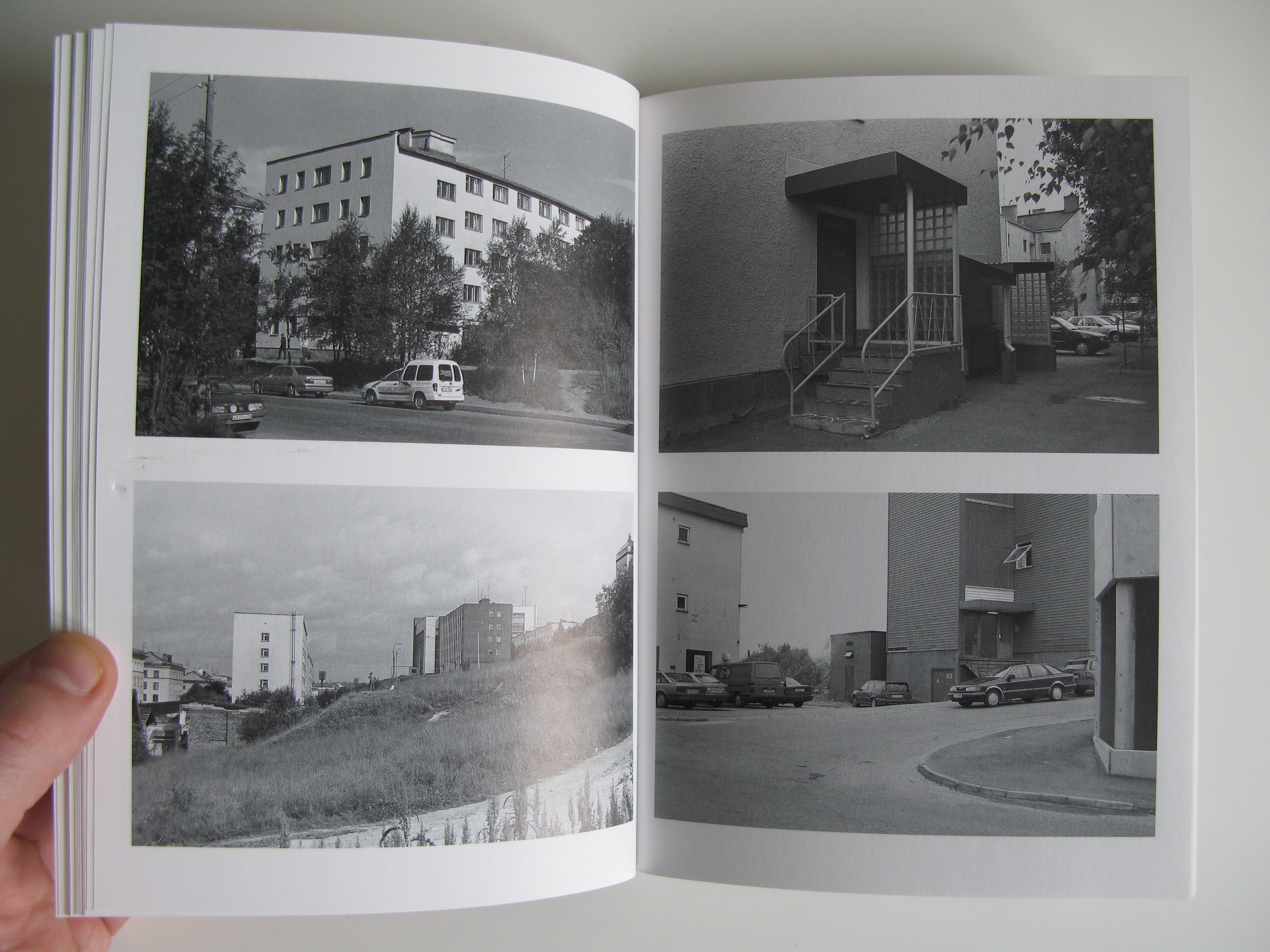

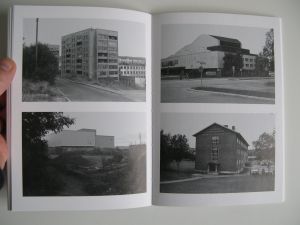

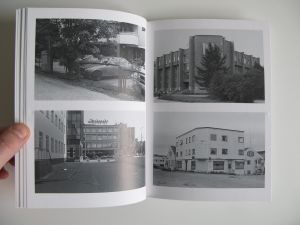

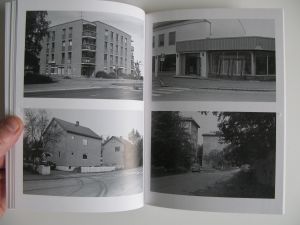

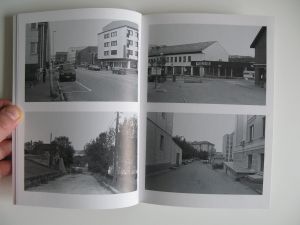

(The project Murmanskrovaniemikirkenes is a photographic examination of architecture and public space in the towns of Murmansk, Rovaniemi and Kirkenes. The project was published in 2004 as a book containing 152 b/w photographs.)

Modernist projects

Murmansk, Rovaniemi and Kirkenes are all architectural and spatial results of socialistic and modernistic projects. They are unique in the sense that they were all destroyed during the Second World War. This situation at the end of the war made it possible to build and plan towns from scratch. The architects involved in these re-erection projects showed an almost heroic belief in that what they were doing. They saw great possibilities for this new space: They would be designing the spatial foundations for a new life.

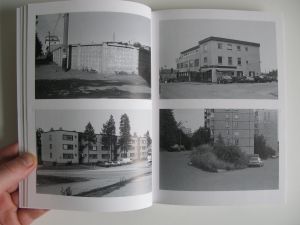

What first drew my interest to these towns and their archtecture was the fact that in these towns, there had been an opportunity to carry out the modernist project in full. I expected to find utopian narratives from the post-war period, obvious and clear in the way that the socialist and communist states had shaped the spaces of their towns. To study these landscapes and towns in hindsight is interesting because we know the outcome of the "experiments" created them. When considering the Soviet Union we know the "outcome" of these buildings, or at least of the project that produced these buildings. This gives us a knowledge that we can project onto the spaces where the fantasies of a certain period remain sedimented in the buildings. In many ways the architecture reads like an historical archive of cultural, social and political interests.

Representation

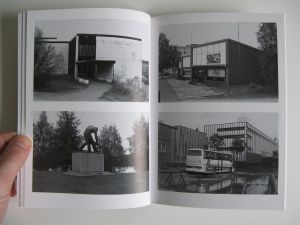

These days the media is crowded with representations of design and architecture. Often I find that these images/representations are pure surface. By this I mean surface that has no content but to be desired, desired as a commodity. Either as a dreamworld, or as a commodity for purchase.

It is interesting to look at a magazine like Wallpaper* where space and buildings are shown as objects of desire. This way of representing space re-presents us with architecture (and design) as a commodity: something worth buying, something worth seeing, something worth paying for. In this sense it is the architectural wrapping that is important and not the content. In the words of Hal Foster, these are spaces that evoke "an individuality that seems more exclusive than democratic" and that appear as "sites of spectacular spectator ship, of touristic awe."

So what has Wallpaper magazine to do with three frozen towns in the back of nowhere? The architecture (and design) of the functionalist/modernist movement now has become a style. The social and political programme of the functionalist movement is out of focus, and funcionalist architecture and design is being recycled as trendy objects. Architecture returns as image and commodity, subject to changing fashions, markets and tastes.

As a photographer I contribute to the enormous amount of images that describe urban reality. I believe, however, that the strategies that motivate my description of these towns are not necessarily the same as those prescribed by the state or the market forces. Or, for that matter, the places and routes that Wallpaper magazine would have liked me to navigate after. Maybe it is possible to describe such a difference as the difference between architecture as image and commodity and architecture as an everyday space where everyday life and experience takes place.

Pictures and photographs suggest a way of looking at the world, suggest a certain perspective. My project has as its starting point that it is possible to change the way one percieves an object through the way one describes it: to change the meaning of the object through description. In other words: a precondition for working this way is that one believes that it is possible to change the experience, perception, meaning and reading of the subject represented.

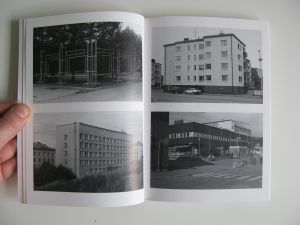

Walking

The Situationists were concerned with a critique of lived space and developed the method of the dérive, which was a kind of experimental urban nomadism. The point of the dérive was to overthrow the homogeneity that the Situationists saw in the city. The dérive was an activity that rewrote the space of the city by a different set of meanings and desires than the ones of consumer society or state. This was achieved through imaginative reconstructions of places and spaces in the city.

I wouldn't say that the way I have operated while walking through these towns is entirely original and imaginative. Somehow it combines different ways of using the town that already exist: such as that of the pedestrian or the tourist. The pedestrian walks and the tourist photographs. In addition the tourist often gets lost. According to Walter Benjamin it is necessary to "get lost" in the city. But for Benjamin there is a difference between not finding one's way and getting lost. Getting lost "properly" requires practice.

Both the Situationist dérive and Benjamin's "getting lost" imply an alternative agenda/itinerary when moving navigating the urban landscape. For instance, both shopping, tourism and public spaces have spatial programmes that control and direct the behaviour and movement of the individual. However, by straying from these programmes, i.e. not being there to shop, not being there to see the sights, or not going to some public office, it is possible to find and explore new knowledge and perspectives.

Maybe it is possible to suggest that this kind of walking lacks purpose, or maybe more precisely, that it has another purpose. A purpose that challenges the "usual" prescribed pattern of moving through the city to a predetermined destianation. Street level walking can be a kind of boring everyday experience that doesn't take into consideration the grand views of state buildings, town squares and shopping centres. Photographing houses and spaces that one finds when walking like this should be able to show visual traces of a walk that is freed from the usual itineraries of urban space.

Archive

The archive that I was making produced likeness and difference between the towns. The archive was to be democratic in that no buildings or spaces were more important than the others. A horisontal representation, showing equality, repetition and rhythm. It was a visual archaeology that encouraged close investigation and activated the eye of the viewer. The meaning came from the images themselves, and in the comparison of the individual photographs.

The archive had two effects: It was possible to see the likenesses between the buildings and the spaces. At the same time this comparative presentation also made differences between the buildings and spaces more visible. I still see this as a part of the way the work works, but after a while it seemed as if the single image stopped being interesting in itself, and that the comparison between them only had meaning insofar as the likeness produced by the photographs created a feeling of confusion.

Upon closer inspection it seemed that it was the connection between all the images that carried the meaning of the project. When turning the pages of the book the pictures merged and seemed to suggest a new space.

Imaginary geography

In the end the juxtaposition of the images does more than create new meaning: it also makes a new imaginary space. An imaginary terrain made possible by the interweaving of the different streets, buildings and spaces. Walking thus becomes an act of connecting, of weaving the places together. The walking (and the photographing) creates a spatial discontinuity; through the connections it makes, through the connections it makes between buildings, houses and spaces.

Maybe it is possible to suggest that the fragmentation of these cities within the archive and the book allow for a new construction. This (re)construction suggests a new space, a new geography, a new topography. This new space is imaginary and moves across national and cultural borders.